By Benjamin Malesevic and Skander Alexander Mraida, 1st of May 2023

Over the last decades, cities have grown

tremendously. They are becoming more densely populated and many people are

starting to lose connection with nature. Therefore, the provision of green

spaces in cities is greatly valued by urban residents. Access to ecosystem

services provide many benefits such as improving physical and mental health and

providing recreational opportunities. Moreover, due to climate change and the

increasing urban heat island effect, people living in cities desire frequent

and easy access to urban green spaces. According to Brussels Environnement,

about 50% of the Brussels Capital Region is covered by green space and about

30% of green spaces are considered to be private gardens. Nevertheless, are all

residents able to use green spaces and benefit from the services they have to

offer?

Several studies have shown that development of

urban green spaces in low-income neighbourhoods are less pronounced. Looking at

the maps below, it confirms that the city centre of Brussels and the Northwest

of the city have a poor degree of vegetation. Municipalities like Anderlecht,

Molenbeek and Sint-Joost-Ten-Node are seen as low-income neighbourhoods and are

often referred to as the “poor croissant of Brussels”. Residents of these

neighbourhoods have to travel substantially further to enjoy large urban green

spaces compared to the more affluent neighbourhoods in the South of the city.

This shows that there was little attention paid to the implementation of green

spaces in these neighbourhoods during the development process of the city.

Historically, accessibility to urban green spaces in the past was only reserved

to the wealthy elite like the bourgeoisie and these previous urban developments

are still seen today. Former industrialised areas such as the canal zone and

the densely built-up city centre have much less space to implement parks and

other urban green spaces. Even if there are green spaces available, you can

clearly see that they are characterised by lower quality and people enjoy using

these spaces less compared to the large parks located in the South of the city

such as Bois de la Cambre and Parc Cinquantenaire. This makes nearly two third

of the population have no access to high quality green spaces (Phillips et al.,

2022; Rodriguez-Loureiro et al., 2021; Schindler et al. 2018; Stessens et al.,

2017).

Figure 1: Map of vegetation index

in % of Brussels in 2020 (left) and map of average income per capita after tax

in €, in 2019 (right) (Source: BISA).

But why is equal

access to green space important? According to VUB researcher Charlotte Noël,

there is a correlation between air pollution in areas which lack urban green spaces.

Even when there are green spaces available, not everyone respects them equally.

“There are people that are not

respectful towards their environment here. A simple empty beer bottle can

create a subjective feeling of insecurity which keeps people from using public

spaces, not only but especially for women.” (Charlotte Noël, 2021)

Urban green

spaces which are not well maintained will discourage people from visiting the

park more frequently and their accessibility to green spaces will become

limited. For example, when you see empty beer bottles and other trash left on

the ground, it will make people feel uncomfortable and unsafe. This is the case

for several parks or smaller urban green spaces located in the city centre

while larger urban green spaces in the South of the city are perceived as

cleaner and more attractive. Therefore, from these characteristics it also

emerges how accessibility is not only derived by one’s positionality but also

from other factors, like cleanliness and safety.

Subsequently,

the study mentioned that pollution plays an important role in the healthiness

of a park. In the maps below, we can see the increasing air pollution in the

city centre due to the presence of smaller urban green space. Hereby, residents

living in “the poor croissant” of Brussels are especially disadvantaged

compared to people living in the South of the city. To eliminate this

inequality, it is important that we know who has access to green spaces and who

does not, so that we can eliminate this inequality.

Figure 2: Annual mean concentrations of pollutants (µg/m³)

(left) and percentage of houses with very low comfort in % (right) (Source:

Noël et al., 2021).

“It is

important that we know who has access to green and who does not, so that we can

eliminate this inequality.” (Amy Phillips VUB, 2019).

However, to eradicate this social inequality

and environmental injustice, it is important to identify the perception of

urban green spaces and who uses them. According to the Co-Nature project, there

is a classification of residents who use urban green spaces. On the one hand,

there are social users who visit city parks to socialise, hang out with friends

and family, go to events, or bring their children along for some playtime. On

the other, there are people who value nature and use urban green spaces to get

in touch with it, take advantage of ecosystem services, and seek out peace and

quiet in the city. Compared to social users, nature-oriented users are also

more likely to travel further to enjoy the necessary connection to nature (CO-NATURE,

2019).

Figure 3: Distance travelled by

residents to their selected UGS (Source: CO-NATURE)

Social disparities in access to green spaces

present a significant challenge for the Brussels Capital Region. However, the Brussels

Government is taking actions to improve the provision of green spaces and its

quality without creating disparities of accessibility. The city is planning on

creating ecological corridors to connect existing urban green spaces to

increase biodiversity. Moreover, they are planning to implement better mobility

connections to large urban green spaces so more residents can enjoy the

benefits of urban green spaces (Perspective.Brussels, 2022).

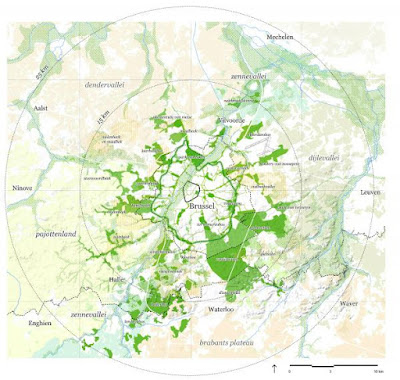

This is part of the OPEN Brussels project,

which aims to create a vision for enhancing an open space network that is

sustainable and regionally coherent with an emphasis on biodiversity, water,

coolness, silence, recreation, and active mobility. This concept is based on

the widely held belief that open space is a vital part of the city.

Furthermore, the Brussels Government believes that an ecological optimisation

of the Brussels open space network is the appropriate way to ensure, in

particular, further urban densification in a qualitative way. Additionally, it

contributes to social cohesion, the quality of life of the Brussels residents,

together with resilience, attractiveness and overall value of the city (Perspective.Brussels,

2022).

Figure 4: Visualisation of

developing open green space in the Brussels Capital Region (Source:

Perspective.Brussels).

To develop these projects successfully,

community involvement and participation should be taken into account and

bottom-up initiatives need to be supported, guided and directed. To ensure that

everyone has equal access to high-quality green spaces, a comprehensive,

egalitarian and long-term strategy to resource allocation and community

engagement is necessary. By doing this, we can make the urban environment more

sustainably just and healthy for everyone who lives in the Brussels Capital

Region.

References

Bruzz.

(2019, September 26). VUB-onderzoek toont aan: Brussel is groen, maar niet

voor iedereen. Retrieved

April 22, 2023, from https://www.bruzz.be/samenleving/vub-onderzoek-toont-aan-brussel-groen-maar-niet-voor-iedereen-2019-09-26

CO-NATURE.

(2019). Green space access and satisfaction in the Brussels Capital Region.

Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://www.co-nature.org/accessibility-to-ugs

Da Schio,

N., Boussauw, K., & Sansen, J. (2019). Accessibility versus air pollution: A geography

of externalities in the Brussels agglomeration. Cities, 84, 178-189.

Noël, C., Landschoot, L. V., Vanroelen, C.,

& Gadeyne, S. (2021). Social barriers for the use of available and

accessible public green spaces. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 102.

Perspective.Brussels.

(2022, February). Openruimtenetwerk in en rond Brussel. Retrieved April

22, 2023, from https://perspective.brussels/sites/default/files/open_20220203_brochure_nl.pdf

Phillips,

A., Canters, F., & Khan, A. Z. (2022). Analyzing spatial inequalities in

use and experience of urban green spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban

Greening, 74, 127674.

Rodriguez-Loureiro,

L., Casas, L., Bauwelinck, M., Lefebvre, W., Vanpoucke, C., Vanroelen, C.,

& Gadeyne, S. (2021). Social inequalities in the associations between urban

green spaces, self-perceived health and mortality in Brussels: Results from a census-based

cohort study. Health & Place, 70, 102603.

Schindler,

M., Le Texier, M., & Caruso, G. (2018). Spatial sorting, attitudes and the

use of green space in Brussels. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening,31,

169-184.

Stessens,

P., Khan, A. Z., Huysmans, M., & Canters, F. (2017). Analysing urban green

space accessibility and quality: A GIS-based model as spatial decision support

for urban ecosystem services in Brussels. Ecosystem services, 28,

328-340.

.png)

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment